Writing Simple Python Unit Tests

This post covers how to write your first, very simple Python unit tests.

How the test code is organised

The first thing you need to decide is where your new tests should go. Fortunately Hypothesis tests are organised in a very simple way.

For every file in the the h directory

there’s a corresponding file, with the same filename except ending with _test.py,

in the tests/h directory.

For example the tests for h/paginator.py

are in tests/h/paginator_test.py.

Similarly, every file in the src/memex directory

has a corresponding <filename>_test.py file in

the tests/memex directory.

When you run a test command, such as tox -e py27-h tests/h, pytest finds all

*_test.py files in the tests/h directory (and subdirectories).

For each test file pytest then finds all the top-level functions whose names

start with test_ and runs them. Pytest also finds all the classes whose names

start with Test and for each class runs every method whose name starts with

test_. Any other functions or class whose names don’t begin with test

are not run automatically by pytest, these are helper functions for the test

functions to call.

(For more about how pytest finds tests to run see the

complete documentation for pytest’s test discovery rules.)

In h we tend to put the code in a test in the same order as the corresponding source code in the module under test. The tests for the first function in the module would all go at the top of the test module, one after another, followed by the tests for the second function, and so on. Fixtures and other helpers go at the bottom of the test file.

Organising tests into classes

We often organise tests into classes in h, instead of just using top-level test functions. For example you might put all the tests for a module’s first function in one class, then all of the tests for the second function in a different test class, and so on. It’s easier to see where the tests for one function end and those for the next function begin if each function’s tests are indented under a class. Organising tests into classes also allows us to put helper functions, fixtures, patches etc (all of which we’ll see in later posts) in the classes that use them, which can reduce boilerplate and noise.

Exactly how we organise tests into classes varies. Sometimes it might be as

simple as putting all of the tests for one function into one test class. Other

times we’re writing tests for a class and put all of the tests for that class

in one test class, or separate the tests for each of the classes methods into

separate test classes for methods (this may depend on how big the class is and

how many different methods it has). Sometimes it’s useful to use separate test

classes to test the same code under different scenarios, for example

TestLoginControllerWhenLoggedIn and TestLoginControllerWhenLoggedOut,

because each test class can contain fixtures for that scenario (a test HTTP

request from a logged-in user, or an HTTP request from an unauthorized user)

that are applied to all tests in that class. Choose whichever approach works

best for your tests.

Writing tests

Let’s look at a simple as possible example test first.

h/accounts/util.py contains a

validate_url() function

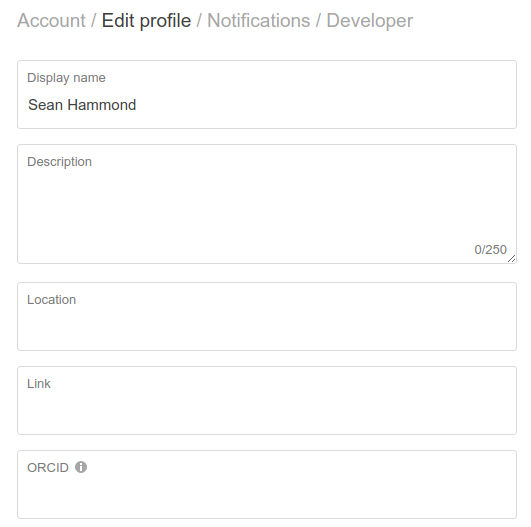

that validates the URLs that users enter for homepage links in their user

profiles. It’s the validation for the Link field in this user profile form:

validate_url() raises a ValueError exception if the string provided by the

user doesn’t look (vaguely) like a URL (this exception is caught by code

further up and turned into an error message that’s shown to the user).

If the URL does look valid then validate_url() returns it, possibly with

https:// prepended to the front of the URL if it was missing.

def validate_url(url):

"""

Validate an HTTP(S) URL as a link for a user's profile.

Helper for use with Colander that validates a URL provided by a user as a

link for their profile.

Returns the normalized URL if successfully parsed or raises a ValueError

otherwise.

"""

...

The tests for this function are in

util_test.py.

Here’s a couple of very simple tests that test that validate_url() returns

https:// URLs unmodified, and that it adds https:// to the start of URLs that

don’t have it:

def test_validate_url_returns_an_http_url_unmodified():

assert validate_url('https://github.com/jimsmith') == 'https://github.com/jimsmith'

def test_validate_url_adds_http_prefix_to_urls_that_lack_it():

assert validate_url('github.com/jimsmith') == 'https://github.com/jimsmith'

These are examples of the simplest possible test functions. They just call the function under test, passing in a certain argument to the function, and then use Python’s assert statement to test something about the function’s return value.

If the expression passed to the assert statement evaluates to False

(that is, if validate_url() doesn’t return the URL that the test expects),

then the assert statement will raise an AssertionError and the test will fail.

Otherwise the assert does nothing, and if the test completes without an error

being raised it passes.

(For more about how the assert statement works, see

Dan Bader’s Assert Statements in Python tutorial.)

When an assert fails pytest

outputs useful information about the failure

such as the values of the two sides of the expression (the result given by

validate_url() and the result that the test had been expecting) and the

differences between them.